Leonid Flyat

Educator Rodak Isaak Izrailevich

To Maya Isaakovna, the devoted daughter

“RODAK Isaak (Itskhok), teacher. In the mid–1920s moved from Riga to Kiev, where he worked in the Institute of the Jewish Proletarian Culture at the All-UkrainianAcademy of Sciences (VUAN), section of the theory of pedagogics. Published articles on pedagogic subjects in the journal Ratnbildung (Kiev) and other periodicals. The author of textbooks on the Yiddish language and literature for Jewish schools: Literature (for the 5th and 6th classes), Kharkov–Kiev, 1932), Shprakh (for the 5th and 6th classes, Kharkov–Kiev, 1932), Grammatik (in 6 volumes, Kharkov–Kiev, 1933–1936), Arbet af Shprakh (Work on Language) – training manual), etc."

This article from The Russian Jewish Encyclopedia (Moscow, 1995; vol.2) should attract the attention of the reader searching for any information on the Jewish scientific institutes in Kiev during Soviet times. At the same time it will certainly be disappointing by its brevity. There is no doubt that this article is based on a corresponding publication in Yiddish of the American bibliographic edition. But there is no answer to the question of why the authors of the Encyclopedia in Russia were satisfied with such a limited biography of Isaak Rodak and did not make use of the archival documents that seemed to be easily available to them.

For those to whom the archives are inaccessible, there exists, thanks to progress, the Internet. The name of the teacher Isaak Rodak has been mentioned in two reports placed on

one of the Odessa websites, for example, in the presentation Higher Jewish Education in the Soviet Odessa by historian V. Levchenko. But the most rewarding of the Internet finds for me, as it turned out later, was the information about Maya Isaakovna Rodak, a Muscovite, participant in the war of 1941–1945, physicist and scientist, after graduating from the Moscow State University in 1949. I was fortunate to get acquainted in absentia with Maya Isaakovna, who turned to be the daughter of the teacher Rodak; I started corresponding with her and received her consent to publish an extended biography of her father based on the memoirs and documents from the Rodak family archive. It is noteworthy that all this takes place on the eve of the 120th anniversary of Isaak Rodak's birth date, the anniversary that is honored by Jewish tradition.

On June 24, 1890, in the family of Israel Rodak, a roadman in the small town of Kobrin in Grodnenskaya gubernia [province], a son Isaak was born. From his childhood he aspired to knowledge, and his parents approved this disposition. He entered a city school in Brest and studied there till 1905. Revolutionary moods of that time inspired young Isaak. Together with two friends he distributed leaflets and illegal brochures at school, where they instigated a strike as well. Eventually, all three young men had to leave school voluntarily to avoid being expelled with the wolf ticket (a document forbidding admittance of its holder to any educational institution) and thus to preserve their opportunity to continue their education in the future.

In 1906, the following year, he passed exams in the Brest private Commercial School (College), renowned not only for a high level of teaching of exact and natural disciplines as well as a spirit of liberalism but also for the absence of the notorious percentage norm for Jews. Besides regular studies, Isaak devoted much time to reading books of Russian authors, then giving reports (On Bazarov’s nihilism and others). To support himself and his studies he worked as a tutor, but his means were not sufficient. For the senior classes his tuition was paid by a philanthropic society “for relief aid to destitute pupils.”

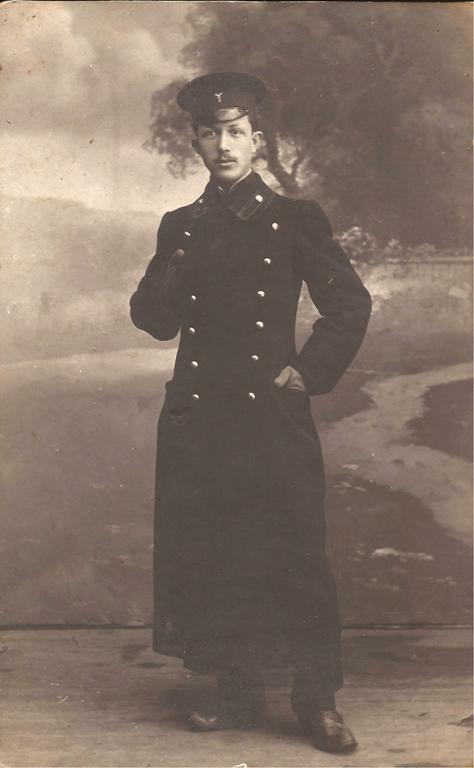

After graduating from the commercial school in 1910, Isaak Rodak joined the infantry of the Russian army. As he was a volunteer with secondary education and had not yet reached the official military age of 21, his enlistment was reduced by two years, and thus he was discharged in 1911.

20-1. In the commercial school 20-2. A volunteer

Isaak Izrailevich then became a student of the economic faculty of a private commercial institute in Kiev. One of the reasons that dictated this choice was the condition that the commercial school graduates were accepted there without examination. In June 1914 he married Fanya Davidovna Chvirkovskaya, a graduate of the Higher Courses for Women at the Warsaw University, the branch of natural sciences of the physics and mathematics faculty. Isaak had been connected with Fanya for many years since their youth when Fanya studied in Brest grammar school, she lodged in the house of Isaak’s parents.

20-3. Gymnasium student, 1910 20-4. Graduated from gymnasium

20-5 20-5  20-6 20-6

The newly married couple spent a honeymoon at the Czech resort of Kudovo (in the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Soon the war interrupted their retreat, and the young couple had to part for a while. The authorities allowed Fanya Davidovna to return to her parents. And Isaak Rodak, threatened with internment, was forced to move to the West where he stayed in Belgium for some time. In 1915 he managed to return to Kiev and graduated from the Institute. During the last period of the First World War and the following months of revolution and reorganization of the western areas of the former Russian empire, the young Rodaks wandered over Poland and Lithuania, working as teachers in Jewish national schools of Sedlets, Warsaw, Vil’no, and Kovno.

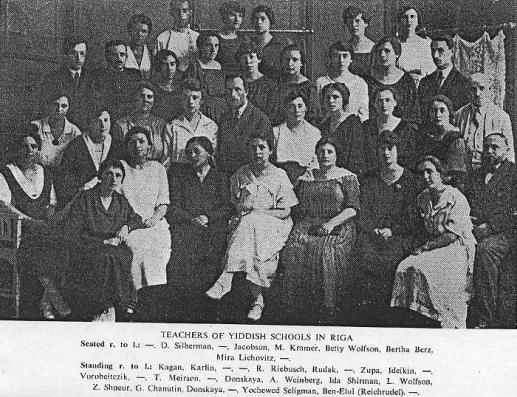

In 1921 the Rodaks settled in Riga. There Isaak taught in a city Jewish grammar school, gave lectures in the Jewish public university, and taught Yiddish as part of the Jewish courses for teachers. He devoted considerable time to public works in the Central Yiddish School Organization (CYShO). Maya Isaakovna is familiar with the book Jewish Secular School in Latvia (New York, Tel Aviv, 1973; in Yiddish), written by Mendel Mark, one of the teachers in Riga. In this book the author summarizes the experience of the Jewish school organization in Latvia. The school’s staff included people of different political views: members of the Jewish Labour Bund as well as Zionists and communists. All of them were enthusiasts of Jewish education and pursued a common purpose: to introduce the pupils into the world of culture using their native Yiddish language, known from childhood.

The Jewish secular school in Riga was organized in 1919. In March 1921, the first Jewish Teachers Conference took place. Following this forum, CYShO was created. Among the most active and erudite organizers of the conference was A. I. Vorobeychik (1893–1942), more known for his later pedagogical and literary activity in Soviet Odessa (1923–1941). He opened the conference and was then elected the CYShO Chairman. He was called to serve in the Soviet Army in the first month of the Great Patriotic War in 1941 and never returned home.

Here is a photo from The Jews in Latvia, Tel Aviv, 1971. Vorobeychik stands in the 3rd row, right, Rodak – in the middle of the 2nd row.

20-7

20-8 Isaak Rodak with the first graduates of the Jewish secular school in 1926.

Rodak sits in the middle row 2nd from the right, near him left is the teacher Ribovskaya, left to her is Isaak Itkin, who probably was a member of the Parents’ Committee. On the back of the photo, an inscription in Yiddish: "Der ershter aroisloz fun der dritter schul 1926" [The first graduates of the 3d school, 1926].

Isaak Rodak, a beginner in the Riga Pedagogical Society, presented a report, On the principles of the new school formation. The report evoked a ready response from the participants, and many issues of the report were included into the Conference resolution. A. Vorobeychik, I. Rodak, Betty Volfson, I. Berza, and I. Brown were elected to the CYShO Executive Committee. When Aaron Vorobeychik immigrated to the Soviet Union in 1923, CYShO was headed by Isaak Rodak. His wife Fanya was also active in public life; she was a member of the First Committee of the Riga branch of CYShO.

In April 1926, on the occasion of the fifth anniversary of CYShO (its chairman by this time was Mendel Mark), the activity of the organization for the last period was summed up at the anniversary session in the reports of I. Rodak (in Yiddish) and Freidberg (in Latvian). And in December, at the Pedagogical Exhibition, Isaak Izrailevich gave a talk Approach and analysis of works of fiction. His last public appearance in Riga was at the congress of pre-school workers. The title of I. Rodak’s lecture was The lesson of the Hebrew language in an elementary school.

The Rodaks were not members of any party but, sympathizing with communistic ideas, watched with interest the successes of Jewish cultural life in the Soviet Union and aspired to get there. In turn, the leaders responsible for the education system in the Yiddish language in the USSR and in Ukraine in particular invited from abroad Jewish teachers who showed loyalty to the Soviet authority.

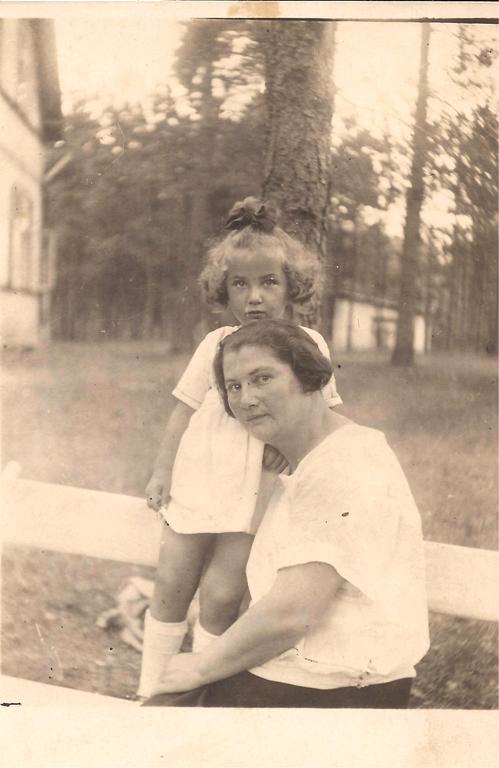

And so, in 1927, the teachers Rodaks with their four year old daughter Maya, left Riga and settled in Kiev. Here is the last photo from Riga, when a group of pupils came to Yourmala (Dzintary, at that time Edinburg) to bid farewell to their teachers.

20-9

Not all persons here we can identify. Standing from left to right: 2nd-Berngard Shnaider, 3-d Lazar Bernstein, 5th-Mosus Itkin, then Isak Brod, Borukh Berkovich, -, Iosif Garfunkel, unknown, Isaak Peretsman.

Sitting Abram Barmazel, Lola Goldin, Zara Rafaylovich, Fanya Rodak, Isaak Rodak, their daughter Maya Rodak (4 years old), Sima Fishberg, Ioshua Ioffe (Koter),Aida Berkovich.

20-10. Near Riga, 1927 20-11 Fanya with her near friend Mariam, Warsaw,1913-1914

At that time CYShO, to which Isaak and Fanya had devoted considerable energy and time, existed for seven more years. It was closed in 1934, when Ulmanis came to power in Latvia. The history of CYShO of Latvia undoubtedly deserves its own distinct and detailed account.

20-12 20-12

20-13 20-13

In Kiev Isaak Izrailevich started to teach in the Podol evening Jewish school No. 17 and at the same time gave lectures to students of the Jewish faculty of the Lysenko Music and Drama Institute. His wife headed the Jewish children's home that occupied a large apartment in the house No. 13, Tereshchenkovskaya Street. One room of the apartment belonged to Fanya, the director, and her family. And their daughter Maya was enrolled in the Jewish kindergarten. It would have appeared natural, but in those days not many figures of the Jewish Soviet culture encouraged their children to learn the Yiddish language. Later the parents enrolled Maya in the first class of the Jewish school No. 33.

In 1929, when the Faculty of Jewish Culture in VUAN (All-Ukrainian Academy of Science) became the Institute of the Jewish Proletarian Culture (IEPK), Isaak Rodak was accepted as the post-graduate student of the pedagogical section headed by professor Yakov (?) Reznik. There Isaak was appointed the foreman of the team responsible of preparation of textbooks for the Jewish schools, as documented by the bibliographic data. In 1932, several textbooks on the Yiddish literature and language were published, and I. Rodak was among the authors. Literature for the 5th class was prepared by him together with the poet and teacher Abram Velednitskii. The same textbook but for the 6th grade was written in collaboration with Avraam Abchuk and Moishe (Moisei) Mizhiritski. And Aaron Gelbman participated in preparing the textbook Grammar (part 1, Morphology, 5th grade; part 2, Syntax, 6–7th grades). In the publication list of I.I.Rodak there are also the manual Working at the language and some the pedagogical articles published in the journal Ratnbildung (Soviet Education).

By the summer of 1932, Isaak’s postgraduate study was completed. The following document was then prepared:

"The bearer of this, com. Rodak I. I., who has completed postgraduate studies at the pedagogical section of the Scientific Research Institute of Jewish Proletarian Culture of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, according to the order No. 90516/kp of 25.04.1932 of the National Commissariat of Education of the USSR, is sent for constant work as a lecturer to the Jewish sector of the Odessa Institute of Social Education.

Director of Institute /prof. Liberberg/

Scientific secretary /L. Shekhter/

Notable is the fact that the IEPK directors did not implement the Narkomat order hurriedly: Isaak Izrailevich was sent to Odessa only in the second half of October. Probably the Kievers did not wish to lose their valuable expert. But, alas…

In the Odessa Institute Rodak read lectures to students on pedagogics; starting from December 1933 he got involved in administrative work and in addition to his job also fulfilled the duties of the assistant director at the correspondence sector [extramural education]. Fanya Davidovna started working at the faculty of psychology. But then came the unforgettable year of 1937. “Enemies” were searched for everywhere. Due to the mere fact of recent residing in bourgeois Latvia, I. Rodak became "a suspect [shady person]." In February 1937, the newspaper Chernomor’ska kommuna (Black-sea Commune, in Ukraine) printed a note with this threatening heading: “For how long will the people’s enemy Rodak destroy the correspondence sector?" Fortunately, the publication caused only administrative consequences reflected in one line of the work-record card (work-book). On the 15th of the same month, Isaak Rodak—at his own will—was discharged from the correspondence sector; yet, as is remembered by his daughter, for some time he continued to work in the Institute as a technician. Fanya Davidovna, dismissed from the Institute, managed to find work as a schoolteacher.

But sooner or later everything comes to the end. When the "iron" people's commissar Yezhov had done his dirty deeds and “disappeared," the mass psychosis on the “people’s enemies” search somewhat subsided in the country. In the life of the Rodaks some positive changes occurred too: The head of the family, as is written down in his work-book, from 1938–39 academic years, was appointed to the position of senior lecturer of the Faculty of Pedagogics, and Fanya Davidovna became a teacher of the German language at the University starting in 1940.

On arrival to Odessa, Isaak Izrailevich focused on summarizing his pedagogical experience. It is now hardly possible to find how many times the dissertation title changed so as to meet the requirements of quickly changing Soviet reality. We point out incidentally that for different reasons the system of Jewish education of all levels shrank like magic skin [La Peau de chagrin] in the whole country and in Odessa in particular; eventually it come to the end in 1939 with liquidation of the Jewish sector and, in fact, of the sectors of other national minorities in the Odessa Teachers Training Institute. The dissertation Education of conscious discipline in the Soviet school completed by I. I.Rodak in 1940 was submitted to Kiev University for competition for a scientific degree of the candidate of pedagogic sciences (Ph.D. in pedagogic science).

But … the war with Nazi Germany began, and not only did the dissertation defense have to be put aside. At the end of July 1941 Isaak Izrailevich was mobilized to dig entrenchments near Odessa, while Fanya Davidovna with their student daughter left to the east—basically on foot—with a group of university colleagues. In Kherson the family was reunited, and together they reached the other coast of the Dnieper River. By this time it became clear to them that the organized evacuation plans had fully failed and that only their personal initiative would allow them to be rescued. In October the Rodaks reached Bashkiria. Skilled teachers and the young student were directed to work in a secondary school of Ermolaevka, a district center in Bashkiria Autonomic Republic (BASSR). In spring 1942 the parents saw their daughter off to the army and, living in misery, worked at the school for one more year. But they managed to find the high schools in which the spouses had worked before the beginning of the war. The University and a Teachers Training Institute of Odessa were then located in the small Turkmen town of Bajram-Ali, and both teachers got a call for work from there.

With the clearing of Odessa of invaders, return of enterprises, establishments, and people began. As is written in the Memoirs of the historian professor S.Y.Borovi, not all the lecturers of the Odessa high schools had the right to return to the city; the idea of percentage norm was revived. The Rodaks knew what this felt like: They were entrusted with an honorable mission "to restore the Donbass higher school destroyed by the war," and specifically to work in the Teachers Training Institute of Artemovsk. But in everyone’s life there is a place for something that brightens it up from time to time. Fortunately, the original pre-war dissertation was found, in 1946 Isaak Izrailevich defended his thesis, and the following year the candidate of pedagogical sciences I. I. Rodak was given the rank of the senior lecturer.

In 1951 Isaak Izrailevich, having almost twenty-five years' seniority, reached the pension age and decided to leave Ukraine, where the struggle against "cosmopolitans" had become intolerable for him and especially for Fanya Davidovna, and they looked for a place of employment in the Russian province. Senior lecturer I.I.Rodak worked for five more years in the Faculty of Pedagogics of the Teachers Training Institute in Tambov.

Many pupils exchanged letters with Rodaks’ and used to meet them during their all lives. Here is a photo of 1953. Their daughter Maya and their pupil Lola Itkina (Goldina) came to Tambov from Moscow. Lola saw Fanya for the last time.

20-14 20-14

In December 1954 Isaak Izrailevich became a widower and in 1956 completely retired and moved to Moscow where he lived with his daughter Maya.

In Moscow Isaak Izrailevich did not get the pleasure of a "well-deserved” rest but became a non-staff employee of the Academy of the Pedagogical Sciences in order to continue being involved in the activities of teachers and pupils in Moscow schools. Judging by the book Cognitive Problems in Learning the Humanities (Moscow, 1972, I. Y. Lerner, Ed.), in which Rodak’s article Pupil’s questions in the educational process was published, Isaak Izrailevich cooperated with the Laboratory of Didactics of Humanities Education. Before this, his articles were published in the journals Soviet Pedagogics and Radian’ska shkola (Soviet School, in Ukraine), and in 1969, the brochure Creative Activity of Pupils during Training was published as part of a series Scientists—to Teachers.

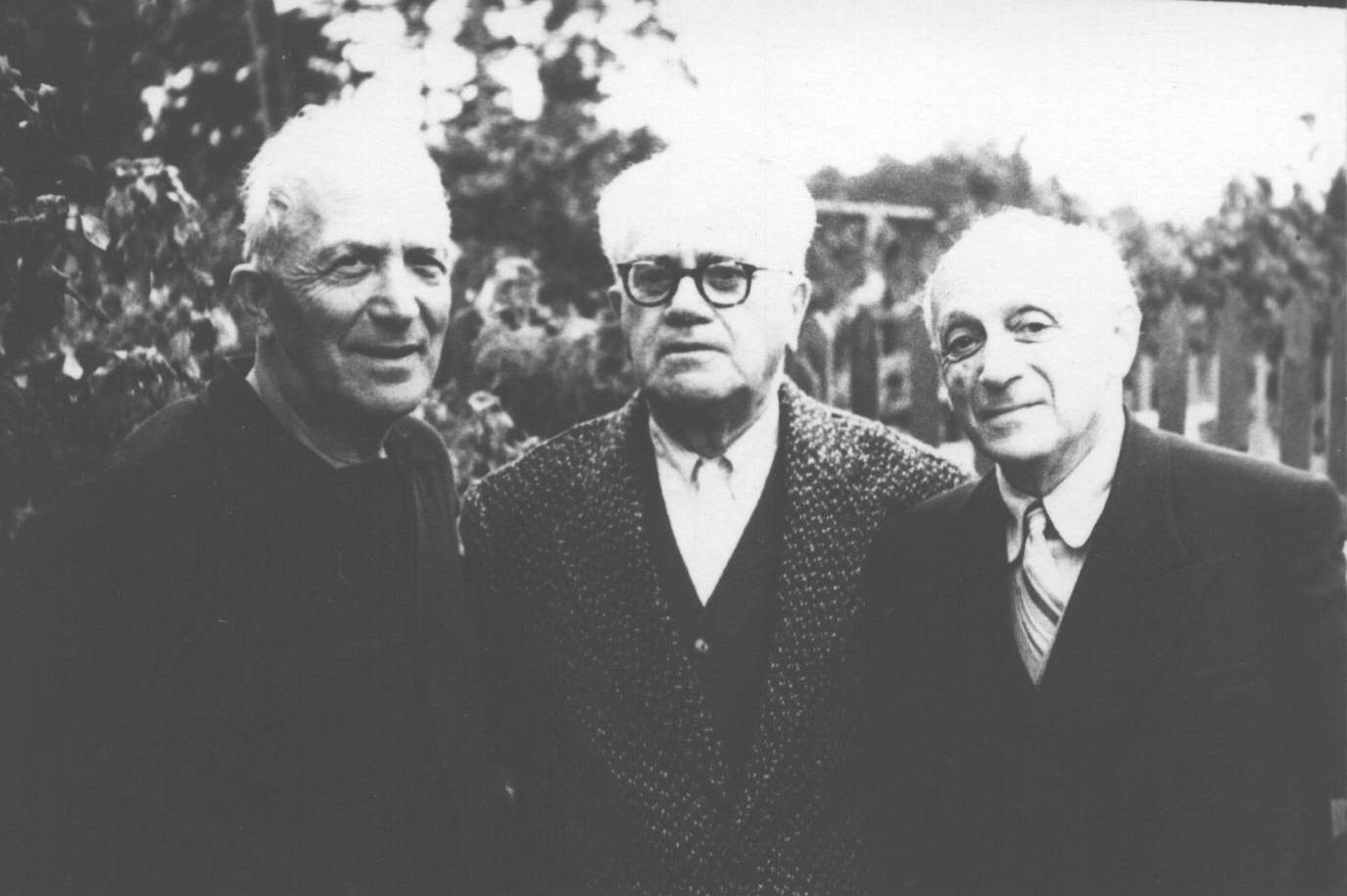

In the 60-ies I.I.Rodak visited Riga and met with his collegues and pupils of that school.

20-15.With Itsik and Tina Berz 20-16 With Aron Reshin (math)

(Isaak Berz was director of and Israel Braun (Yiddish tongue and and gymnasium) Jewish history)

20-17 20-17

The photo is named Yurmala 60. We see here the team returning us to the photo 1927. Left to Rodak Riva Shemer, from the right side I.Garfunkel, B.Berkovich, L.Itkina, I.Brod, A.Barmasel.

Isaak Izrailevich renewed dialogue and correspondence with his fellow workers in Kiev IEPK (Institute of the Jewish Proletarian Culture) Moisei Maidansky and Khaim Loitsker. He made the acquaintance of another Jewish philologist, Muscovite Alee Fal’kovich. He became the reader of the journal Sovetishe Heimland (Soviet Homeland) that published its first edition in 1961. In his last years Isaak Izrailevich had very poor eyesight, which proved very frustrating to him as he could not work and read as he had been used to doing previously.

Isaak Izrailevich Rodak died on July 28, 1981, in his 92nd year, after a massive heart attack.

Translation: Antonina Dunina-Barkovskaya & David Jaman

Cоздание сайта: SAMOMU.RU |